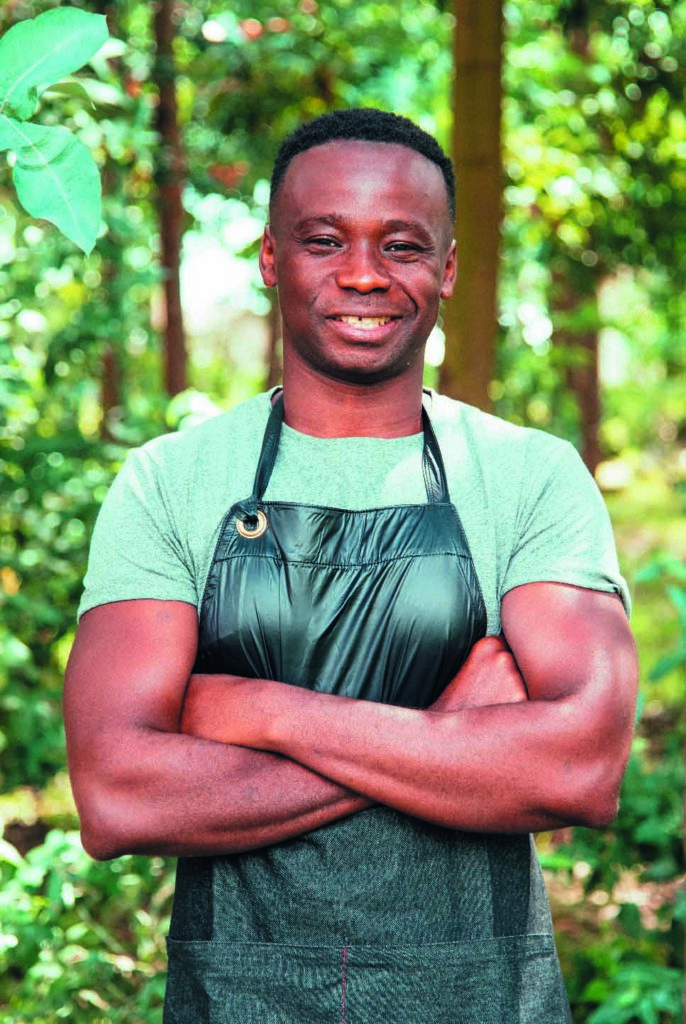

Chef Dieuveil Malonga is a shining star in the international foodie firmament. In 2018, he was ranked 6th by Forbes magazine in their 30 Under 30 – where he was described as “the Congolese chef whose startup is taking African cuisine to the world”. When he is not feeding the gourmet glitterati in his eponymous Paris eatery, Restaurant Malonga, Dieuveil can be found travelling across Africa staging posh pop-ups and compiling a continent-specific spice map.

Born in the village of Linzolo in the Republic of Congo (formerly Congo-Brazzaville) and orphaned as a small child, Dieuveil says his earliest food memories involve “my grandmother, who was pretty famous in our area because she cooked great saka saka [cassava leaves] and liboke [banana leaf-steamed treats], which she sold by the roadside”. He adds that “even in that simple setting, her food was innovative. In Congolese cuisine, it is rare to mix meat and fish; yet she did just that. I think perhaps my interest in fusion and my willingness to try unusual combinations come from her”.

His family’s fondness for fusion may go even further back. Dieuveil explains that in his mother tongue, Lingala, the meaning of his surname implies plurality. “It can be roughly translated as the strength that comes from uniting a diversity of people. That is what I do. Maybe my cooking style was fate,” he says.

After the passing of his grandmother when he was a teenager, Dieuveil met a German family who offered to adopt him. “I was so excited because I imagined that Europe would be like paradise, but I went there in November and it was so cold. Additionally, coming from a country where the food is all about bright colours and generous spices, I was traumatised when I was given potato soup; I didn’t like it!

“My host family then took me to African shops in the country where I bought the same ingredients that my grandmother used in Congo. This gave me a way of staying true to myself. I started fusing African and German products and, after a while, I found ways to make the potato soup really tasty!”

Teenage cross-cultural cooking experiments led to studies at Adolph-Kolping-Berufskolleg, a leading culinary institute in Münster, a university town in Germany’s western Westphalia region. After this, Dieuveil worked at several Michelin-starred German restaurants including Schote, Life Berlin and Aqua. At each eatery, he took his passion for Afro-European fusion with him because he always felt that he wanted to share “the endless wonders of this garden called Africa to reveal its many flavours and merge them so as to compose a harmony of terroirs.”

Such harmony is deliciously apparent in Dieuveil’s recent reinterpretation of Central African classics like mbongo tchobi (a spicy black sauce). As is traditional, Dieuveil makes a velvety textured tomato-based sauce and gives it a distinctive dark hue with ash from burnt hiomi (a woody Congolese spice stick). Other aromatic elements are introduced with njangsa spice and ehuru (calabash nutmeg). Where the recipe is classically made with Congo River catfish, Dieuveil uses scallops.

His version of an achu soup (yellow soup) also offers a similar unification of near and far. The classic palm oil and achu spice – which he describes as “a delicious and unique Cameroonian blend of kangwa [limestone], Penja pepper, rondelle, pèbè [Monodora myristica]” – is reimagined with the addition of roasted shallots, wild pigeon and nasturtium. The chef’s signature dessert is a crumble of cassava flour, cacao and deconstructed brioche set amidst a jewel-like sprinkling of brunoised mango, roasted peanut and purple hibiscus reduction.

Dieuveil says it is his aim with such plates to “write a new story of African gastronomy”. He has no intention of writing this story alone. In 2016, he launched Chefs in Africa as a digital platform, social enterprise and professional network to train and promote culinary talent across the continent. The community currently counts over 4 000 chefs as members.

Asked why he promotes other people’s culinary careers, he says: “I think it comes down to my name, which also suggests diversity, plurality and inclusiveness, as well as the essence of who I am. That is my inheritance and

I want to honour that in everything I do.” www.dieuveilmalonga.com

By Anna Trapido

Photograph by Chris Schwagga